"The trauma of the border has no name" November 24, 2020 – Posted in: Books, Interview – Tags: KAPKA KASABOVA, BORDER

Kapka Kasabova's interview with Athos Dimoulas for Sunday's Kathimerini K.

There is a small village on the slopes of Strandza, behind the Bulgarian border, forgotten by time and steeped in legends. The locals say that every year, "after the spell of apnea", a fireball appears in the sky of the village, some claim it's a dragon and some believe it, some others just laugh, the most reasonable perhaps, but when the author Kapka Kasabova he was in this village some years ago, at the time when the fireball was crossing the sky, he saw a flash in the night and realized that there was no way to explain what he had actually seen. A local, Mr. N., told her the following: "This mountain has spiritual powers. You can't explain some things, and maybe it's better that way."

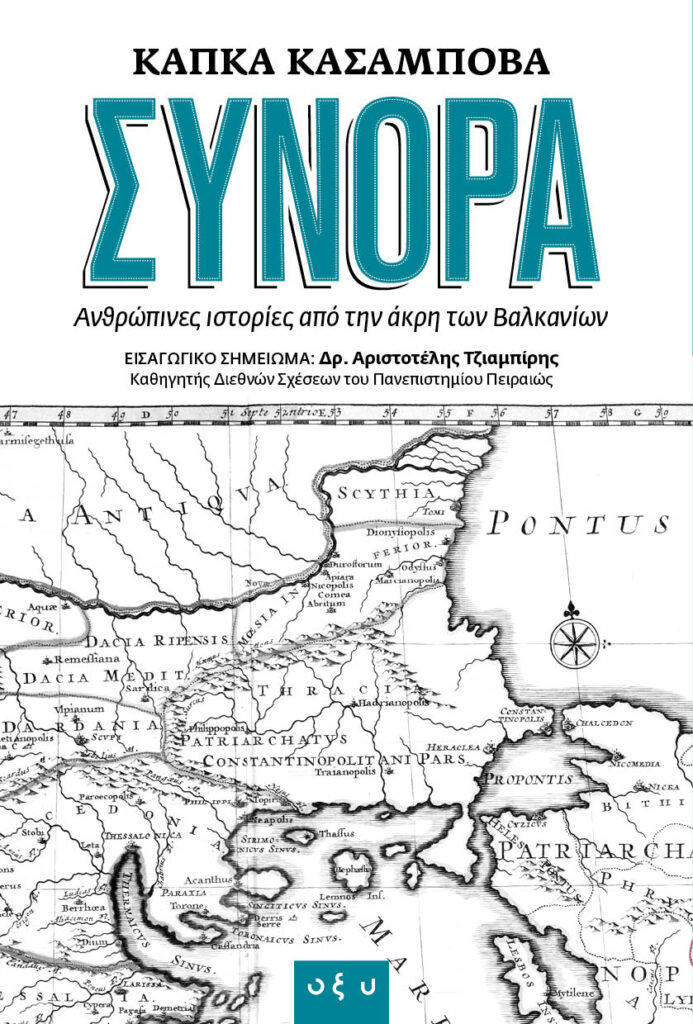

The author had been visiting her country since 1992, but in the period 2014-2015 she made three combined trips to the wider area of the borders of Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. He stayed in abandoned villages, crossed impassable roads, saw how centuries-old customs are still performed, breathed in the beauty of nature and above all he heard countless stories of people he met in all three countries, stories about fireballs, stories about lost souls, stories about History, but also stories about the present, about worries, about life. She recorded all this in a very rare book, adding her memories of her childhood in communist Bulgaria, also adding elements of the place's history, mythology, traditions and language, but also her thoughts about the heavy shadow that spreads over an area that is separated by borders. The "Borders", as the book is called, after a remarkable run abroad, they have just been released in our language by the Acid publications.

I did a lot of research in the English-language press before I contacted her, trying to understand how Western readers reacted to reading about the complex stories of our neighborhood and especially the mysterious legends, such as that of the fireball, that still inhabit some mountainous areas. "Many recognized the universality of some traditions such as the sighing", Ms. Kasabova tells me, "others commented on the role of mythology in the legends of dragons, fireballs or uroki (s.b. the evil eye in Bulgarian), but what was of most interest to Western readers was that these beliefs and practices are still part of the life of the region.' I ask her how she explains it. "People use the metaphysical, the mystical, and generally the otherworldly to heal the borderline trauma that has no name but is omnipresent."

OPPOSITE PATHS

I am copying a few lines from the author's preface for the Greek edition of the book: "At the border, nothing is what it seems. Instead of a mechanism that simply divides in two, the border becomes a labyrinth, worlds within other worlds. People, plans and ideologies disappear as if falling into a black hole, only to reappear in strange ways and perfect timing a generation or two later.' During the Cold War years, Bulgaria's southern border was identified with the border of the Eastern Bloc, where a fence in the forest blocked the path of those who had the bold idea to seek a life in Greece, Turkey or anywhere else - the stories of of the people who were "swallowed" by the mountain run through a significant part of the book, as their traces are still visible through the memories of the locals. Ms. Kasabova remembers that when she was young, she would ask her parents why they couldn't go to that part of the mountain, with her father replying that "we don't have any work over there" and her mother adding that " the forest is full of soldiers.'

It was more than two decades before he could finally go to the mountain and see what was in the forest – the fence, for example, was still standing in places and there were still people trying to get over it, only now they were coming from in the opposite direction: her trips to the border coincided with the height of the refugee crisis. At one point he met three girls of Kurdish origin and saw in their faces "the feeling of being invisible, unwanted, mute, a dismembered soul waiting in a cold corridor of history".

New barbed wire fences are currently being erected on the borders of countries – he tells me there are over sixty border walls in the world today, three times as many as during the Cold War. "The fear of refugees that has paralyzed many Europeans is the fear of tomorrow. The fear of themselves. Because tomorrow, anyone can be on the wrong side of some border. They may become refugees themselves, at the mercy of others, they may become refugees because of a flood, a fire, a collapsed building, or some tyrannical government that they believed would protect them. We are all potential refugees, in one way or another."

THE PEOPLE OF THE BORDER

The stories in the book sometimes start with the occasion of a word, a broken church, a myth or a memory, but they all end up in borders and their people. The author met all sorts on her travels: rangers and treasure hunters, farmers and teachers, hermits by opinion or by necessity. Most of them were willing to open their homes and share their life experiences with her. Was it really so? "Yes, absolutely," he tells me, explaining that this is primarily due to "culture and sentiment," as people in these areas are by nature open and welcoming, like company and want to share conversations, food, experiences.

There is a second reason, however, which he characterizes as "psychological-historical". “Having a stranger suddenly care about you and can actually listen to you is a kind of therapy. Most people never listen. Especially in the Balkans, we prefer to talk, to explain, to interrupt, "I'll tell you how things are", he tells me. "The border people carry a heavy psychological burden, because history has been cruel to them, but also because this is the way the Balkans are. The border is a kind of crystal prism, through which many truths about the true nature of the region are dimly visible. We have failed to face our national history with courage, preferring to deny and cover up our sins and blame our neighbors. This childish behavior which still continues has created strange forms of a collective schizophrenia. People live filled with raw grief, guilt, and a strong need to find a way to relieve themselves."

One of the people she met on the Greek side was Ziko, a four-legged guy of old age and with a mysterious past, who was for a while her guide on the slopes of the Rhodope. At one point he told her that the secret to long life is to have three hearts. One to love others, one to love yourself and one to love the mountains. Because of this interesting theory, I ask her opinion on how much our disconnection from nature has harmed us. "In mountains like Strandza and Rodopi," the author explains to me, "our past and the image of a rural lifestyle are deeply imprinted. Mountains are also a great opportunity for a sustainable future if we are smart enough to protect them and use them properly instead of destroying them to get marble, gold and timber."

THE PERSONAL TRUTH

Through Kapka Kasabova's narrative, the distinction between official and oral history often emerges, and in the borderlands people seem to believe more in their own personal truth. This is explained, as the author tells me, by the fact that “official national versions, especially in the Balkans, offer us a sterile, clean, often dishonest and dangerous narrative about our collective identity. The history I learned at school said nothing about the atrocities during the Bulgarian occupation of northern Greece or the expulsion of the Pomaks to Turkey. "Even when we were watching the persecution of the Bulgarian Turks in 1989, about 350,000 people, on our televisions, we were hearing lies that they were terrorists, that they wanted to take over a part of the country, and many believed them."

Her bitterness is not hidden. The Bulgaria of her childhood was an inhospitable, unsightly, repulsive place. Her family chose to leave after the fall of communism, they moved to New Zealand, she is now permanently settled in Scotland. The Bulgaria she encountered on her travels was not in much better shape than she remembered. Different, but not more attractive. There are places in her text where she seems hesitant about her role in this particular place. How much belongs there? How important is her origin? I ask her if she embraces what is often said, that the writer's homeland is his language. "Yes," he tells me. "Language is a homeland. But we can also say that it is just a tool. We need to connect with something more than the present and ourselves. After all, we belong where we love. This is our true homeland. We must remember what it is that we love, even if it causes us pain – then perhaps we will feel more familiar. And maybe that's why I returned with these trips to the painful frontier of my childhood."