BORDER – Human stories from the edge of the Balkans October 27, 2020 – Posted in: Books – Tags: Hellas, history

Excerpt from his introductory note BORDER, by Dr. Aristoteli Tziampiri, Professor of International Relations and President of the Department of International and European Studies at the University of Piraeus.

There is always a friction between borders and human nature. We are fundamentally curious beings who abhor confinement and often do anything to escape danger, persecution and injustice – and yet, borders not only run across the globe, they seem to multiply. "Border zones" (p.25) in most cases, in addition to national (or even nationalistic sometimes), the borders can also be cultural, psychological or even more indefinite, like those that divide what we schematically call West and East.

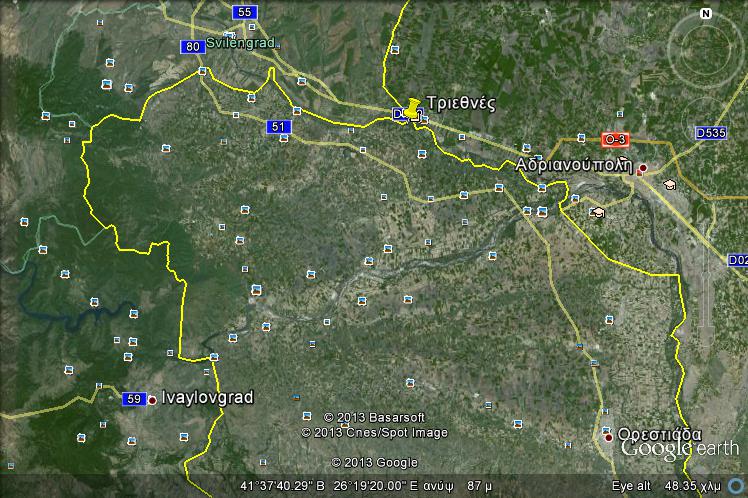

Kapka Kasabova was born and raised in communist Bulgaria, later immigrated with her family to New Zealand and currently lives in the Highlands of Scotland. In Borders, he writes about a region shared between Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey, largely unknown as well as exotic to the wider international audience: what we know as "Triethnes". He chooses this border region "because of the work that has been left in the middle since the Cold War era ... because it is one of Europe's largest wastelands [and] because it has been a crossroads of continents for as long as there have been continents" (p. 24). She also recognizes that her choice will allow her to demonstrate all the absurdity and tensions of the political and ideological borders of the Cold War. As he characteristically notes, at that time in Triethnes "the Turks were worried about the Soviets, the Greeks about the Soviets and the Turks, and the Bulgarians about everyone else" (p. 147).

It is difficult to describe this wonderful book. Part of it is devoted to Bulgaria's so-called "Red Riviera," where Kasabova vacationed with her family and vacationers from other European communist bloc countries. Most were looking for relaxation, but others were looking for an opportunity to cross the border with Turkey and escape to the West. Many were killed, most were arrested, beaten and imprisoned – but this annual 'ritual' did not stop until the fall of the Berlin Wall. As a smuggler explains to her: "When people cross the border they are not fleeing from good... They are fleeing from evil. Sometimes very bad" (p. 262).

Borders is also partly a history book, with rich information specifically about Bulgaria, but also about lesser-known historical episodes and ethnic groups. We learn about Thrace, about the Pomaks, about the Anastenaris of Bulgaria and Greece (as it seems there are quite a few differences between them) and about the Goriani Bulgarians, "the largest and longest-running resistance movement against Soviet state terrorism in Eastern Europe" (p .99). We also learn about the line of defense of Metaxas, a dictator "who was by no means a friend of liberals, books and minorities, no matter how much we talk about the 1930s" (p. 286) and we remember that after the attempt of the Bulgarian regime to assimilate (see suppress) the Turkish population of its territories in the 1980s, at least 340,000 people were "allowed" to leave for Turkey: "It was the largest movement of people in

Europe since World War II. And it happened in time of peace" (p. 168).

Personal retrospective, travelogue, history book, character study, mirror of the international political scene and with abundant references to ancient myths and lore, Borders is made up of seemingly disparate elements, but what binds them together is man's unwavering desire to defy borders and live freely – exactly the same as this book does, ignoring any kind of conventional publishing 'boundaries'. After all, perhaps "the only good thing about borders is that you can cross them" (p. 151).